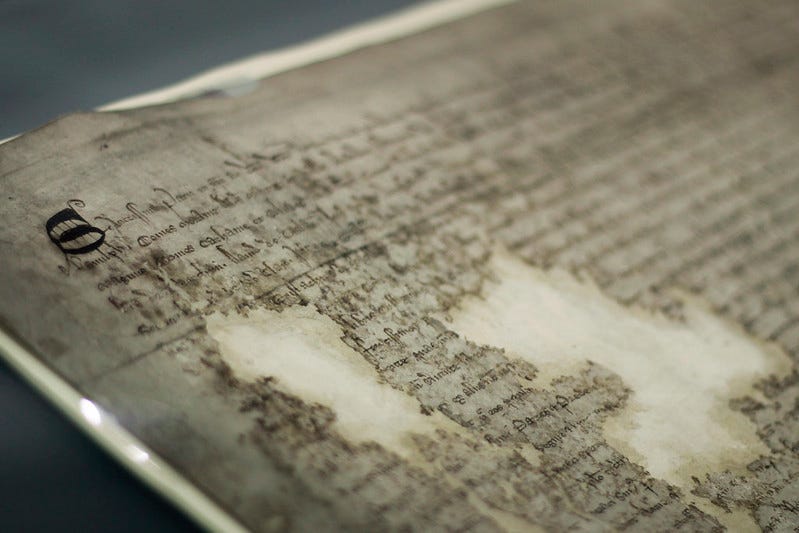

Arbroath, April AD 1320

It has been the better part of a millennium since the hobnailed boots of centurions trod the fields of Caledonia, but Bernard, Abbot of Abroath, looks to the Roman past for inspiration.

As King Robert the Bruce is excommunicated for committing murder in a church, Bernard is writing on behalf of the barons of Scotland to Pope John XXII about the matter of the war with England and English claims of feudal overlordship. To establish Scottish sovereignty, the letter, now popularly known as the Declaration of Arbroath, opens with a description of the ancient Scots and their conquests. The abbot places their origin far to the east in Greater Scythia. (A popular location: Bede located the earliest Picts in Scythia.)

This would be news to Ammianus Marcellinus, the soldier and historian, and other Late Roman commentators who knew the Scots as Irish raiders. In AD 367, the Scots participated in the great ‘Barbarian Conspiracy’. While the Franks and Saxons assailed the coast of Gaul, the Picts (descendents of the Caledones conquered by Agricola), Scots and Attacotti invaded Roman Britannia. The savage Attacotti, also from Ireland, were subject to the Scots. They were infamous for cannibalism; St Jerome noted their predeliction for breasts and buttocks. The Hibernian and Pictish invaders were so successful that two Roman commanders were lost: Nectaridus, the count of the Saxon Shore was killed in a disastrous battle, while the duke Fullofaudes was ambushed and taken prisoner. Augusta (London) was poised to fall to the rampaging barbarians. Then Count Theodosius arrived from Gaul with a small but elite field army. He gradually cleared the British provinces of invaders and launched brutal reprisals that stretched as far north as the Orkney and Shetland Islands.

After leaving mysterious Scythia, Bernard has the ancient Scots traverse the Tyrrhenian Sea (alas, no interactions with the Etruscans or Romans are recorded), negotiate the Pillars of Hercules, and disembark in Hispania. Their sojourn amongst the ferocious and barbarous peoples was heroic, but eventually colder climes called. The Scots sailed westwards but somehow ended up in northern Britannia. There, Bernard informs us, they “utterly exterminated the Picts” - the alliance of AD 367 clearly long forgotten - but merely drove out the Britons. Was the abbot aware that two of King Robert’s leading lieutenants, Donald Campbell, named in the letter, and Sir Arthur Campbell, whose seal was appended to it, sprang from a family that had its origins in the Lennox in the British kingdom of Strathclyde? The Campbells claimed descent from Uther and Arthur of legend. As late as the sixteenth century a Campbell earl of Argyll claimed to be the blood and heir of Arthur, but that’s another story.

Bernard’s fantastical chronicle of conquest is a curious opening for a document revered as a paean to liberty and self-determination, but the abbot demonstrates that it all happened in the very distant past. So long ago in fact, that an extraordinary 113 Scottish kings had reigned and, he emphasises, without a single foreigner breaking the distinguished royal line. Needless to say, King Robert’s mixed ancestry (including a large dollop of Norman), birth in Essex, his recent (and disastrous) attempt to conquer Ireland, and ongoing Scottish raids of destruction into England go unmentioned. Perhaps realising that his account of ancient Scottish aggression and right of the sword narrative undermines complaints about recent English imperialism and atrocities, Bernard is moved to high eloquence. “While a hundred of us remain alive, we will not submit… to the domination of the English. We do not fight for honour, riches, or glory, but for freedom alone which no true man gives up but with his life.” This, of course, is the only bit that modern nativists care to remember; the problematical sections about invasion, colonisation, ethnic cleansing and xenophobia are conveniently ignored. Bernard’s inspiration for this famous passage was a Roman centurion.

Faesulae, November 63 BC

The ex-centurion Gaius Manlius has raised the banner of rebellion and thrown in his lot with the renegade patrician Lucius Sergius Catiline. A small army under the command of Quintus Marcius Rex is sent from Rome to investigate the disturbances in Etruria. Manlius is a man of local importance but Rex is as grand as his name suggests, and so the former centurion sends out envoys. Manlius may be embarrassed by his comparatively humble status, but he is not without eloquence. Indeed, his words, transmitted through an envoy and preserved by the contemporary historian Sallust in The War Against Catiline, will sound familiar. He calls for the cancellation of the oppressive debts that render his fellow military colonists destitute, and then declares: “We ask neither for power nor for riches… but only for freedom, which no true man gives up except with his life.”

Manlius was true to his word. He was killed in battle near Pistoria in early January 62 BC. Many other former centurions, called to the eagle and restored to rank by Catiline, fell beside him. The manner of their death was glorious: not one turned and fled, they died to a man with their wounds to the fronts of their bodies.

Proscriptions and Picenum

Manlius had grown rich in the service of the brilliant and charismatic Lucius Cornelius Sulla. There was plunder from Greece and the East in the campaigns against Mithridates VI of Pontus and his allies (87-84 BC), and equally rich pickings in Italy following Sulla’s victory in the civil war (83-82 BC) and the proscription of his enemies. The very notion of the proscription, a list of public enemies whose lives and property were forfeit, was suggested to Sulla by a primipilaris (a former chief centurion) named Lucius Fufidius. So profitable was this exercise that Fufidius was elevated to senatorial rank and a command in Spain. It was his misfortune, however, to be pitted against Sertorius the One-Eyed, who routed him in battle on the banks of the Baetis (80 BC).

Sulla acquired centurions from the army of another notable player. In November 89 BC, the consul Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo finally captured Asculum in Picenum, the northern focal-point of the great Social War between Rome and its rebellious Italian allies (socii). When the Picente stronghold fell, Strabo rewarded a squadron of valiant Spanish cavalrymen with Roman citizenship. The recipients of the grant were inscribed on a bronze plaque, as were the 59 names of the members of Strabo’s consilium - his staff of legates, tribunes, junior equestrian officers and cadets, and senior centurions. Strabo’s teenaged son, the future Pompey the Great, and the youthful Catiline appear. The final four names on the list are believed to be those of primi pili, the chief centurions of Strabo’s legions: Lucius Pullienus, Manius Aebutius, Publius Salvienus, and Lucius Otacilius.

Their service under Strabo in 90-89 BC would have been dramatic, beginning with a defeat at the hands of the rebels and retreat to Firmum. After licking his wounds, Strabo advanced on Asculum but was defeated again at Mount Falernus, pursued back to Firmum and besieged. With the assistance of another Roman commander, Publius Sulpicius, he broke out of Firmum, routed the enemy and pursued them to Asculum, which he placed under siege. When the Marsi sent an army to relieve Asculum, the Picentes sallied out, but fortune was with Strabo; both of the rebel armies were defeated and Asculum surrendered in due course. The most notable of these centurions was Publius Salvienus, who reappears in Sulla’s service in Greece (86 BC). Plutarch, the biographer of Sulla, portrays him as an ordinary legionary, but the nature of his important mission, to consult the oracle of Trophonius at Lebadaea, required a certain degree rank and status, the kind possessed by a senior centurion. The god, tall and handsome as befitted a son of Apollo, revealed himself to Salvienus and prophesised Sulla’s victory in a civil war (i.e. that of 83-82 BC).

The Senate awarded Strabo a triumph for his re-conquest of Asculum and Picenum. He processed through Rome with his troops and captives (including the infant Ventidius Bassus) on 25 December 89 BC. Salvienus’ transfer to Sulla’s army in Campania probably occurred soon after. At least one of Strabo’s junior officers, the youthful Marcus Tullius Cicero, had transferred to Sulla earlier in the year. Cicero did not remain with Sulla for long. He was completing his tirocinium militiae, a year-long military apprenticeship, before taking up a career in the courts and public office, but he did see action at Nola, where Sulla was conducting operations against the rebellious southern socii, and was struck by the ferocity of Sulla’s legionaries. As a member of an increasingly professionalised military class, Salvienus presumably sought a transfer because Sulla was about to become consul and likely take command of the war in Greece against the forces of Mithridates - a conflict that promised much plunder, glory and the possibility of advancement.

The ranks of Strabo’s army were filled with clients from his estates and Roman settlements in Picenum. The younger Pompey would inherit this clientela, and exploit it to raise three legions for Sulla (83 BC). It is thought that Salvienus originated in Picenum, and another Sullan centurion, the heroic Marcus Ateius, hailed from Castrum Novum on the region’s Adriatic coast.

In 87 BC, under cover of night, Ateius scaled a lightly defended section of the city wall of Athens. Despite his sword breaking when it struck an opponent’s helmet, he held the wall for long enough to allow more of Sulla’s legionaries to gain a foothold and the city was wrested from its Pontic garrison. The army of Mithridates VI generally followed the Macedonian phalangite model, but the king also had a number of troops organised and equipped in Roman fashion. Mithridates had his revenge when he inflicted a terrible defeat on a Roman army at Zela in 67 BC; 24 tribunes and 150 centurions were killed, implying the destruction of four legions. Mithridates’ personal attendants were equipped in the Roman manner and this allowed one of the surviving centurions to infiltrate the entourage of the victorious king and stab him in the thigh. The Roman was immediately surrounded and killed, but his daring deed epitomises the indomitable spirit of the centurion.

It is likely that Marcus Ateius was another transfer from the army of Pompeius Strabo. As well as the incentives suggested above, Ateius may have wished to serve a more charismatic, dynamic and generous commander. Strabo was not loved by his men in the manner of a Marius or a Sulla. In 88 BC, Strabo watched from the sidelines as Sulla took Rome (below). During the subsequent defence of the city from Cinna and Marius (87 BC), Lucius Terentius, a Picente from Firmum and a member of Strabo’s consilium at Asculum, hatched a plot to assassinate the general and his son. Why? The officer was disgusted by Strabo’s inaction and double-dealing; Strabo preferred to keep his troops out of the fight until one side or the other guaranteed him a second consulship. As it happened, the young Pompey foiled the plot, but Strabo succumbed shortly afterwards to the most unusual combination of plague and being struck by lightning.

Roman versus Roman

Before Sulla could embark his army for Greece, the Senate transferred the Mithridatic command to his arch-rival, Gaius Marius (88 BC).

Marius sent tribunes to take control of Sulla’s army in Campania, but they were stoned to death. With the rallying cry of delivering her from tyrants, Sulla marched on Rome. His senior officers were appalled and abandoned him; only Lucius Licinius Lucullus, remained loyal. Junior tribunes and centurions (including, presumably, Salvienus and Ateius) had no such qualms. They would fight to retain their right to plunder the East!

Sulla’s vanguard was led by Lucius Minucius Basilus. He was a man of considerable courage. In an attack that anticipated his daring capture of the Pontic camp at Orchomenus (86 BC), Basilus took the Esquiline Gate by surprise and advanced into Rome but was beaten back by the inhabitants, who took to the rooftops and pelted his legionaries with tiles. Having secured the Colline Gate and Sublician Bridge, Sulla entered the city by the Esquiline Gate. The houses from which Basilus’ force had been bombarded were set alight and the defenders on the rooftops were picked off by archers. Civilian resistance evaporated when Sulla threatened to burn down the whole city, but Marius had mustered a force, which must have drawn on his many veterans, including former centurions, in the confines of the Esquiline Forum.

The Marians put up such a fight that Sulla’s legionaries faltered and fell back. Sulla seized a standard and forced his way through their ranks towards the enemy, shaming the legionaries into returning to the battle. The Sullans rallied, but the Marians held firm. There was a stalemate in the city, but Sulla had legionaries in reserve outside the walls. He sent an order for them to outflank the Marians using the Via Subura and assault them from the rear. Assailed on two fronts, the Marians finally gave up the fight. Marius himself did not. He retreated to the nearby Temple of Tellus and tried to rally slaves, promising them freedom if they fought for him. None were so foolish as to volunteer and the old general slunk from the city.

The Grass Crown

We know little about the centurions of Marius during the Jugurthine and Cimbric Wars, except for the striking example of Gnaeus Petreius. In late 102 BC, he was serving as primus pilus in the army of Lutatius Catulus. Petreius was from Atina and probably owed his advancement to the patronage of Marius, who hailed from nearby Arpinum and commanded a clientela in the surrounding Volscian and Samnite country like that of Strabo in Picenum.

Catulus was Marius’ fellow-consul but he was not an equally talented general. Catulus was forced to retreat down the Adige valley by the marauding Cimbri, and left Petreius’ legion in a fort in the hope that it would hold up the barbarians and allow his main force to escape. This oversized blockhouse was duly surrounded and the tribune in command panicked. When it seemed all was lost, Petreius insisted salvation lay in charging out and hewing a path through the enemy. The tribune was terrified and refused to attempt a breakout. Petreius slew the cowardly commander, harangued the legion and led the charge that cut through the barbarians.

Despite murdering his superior, there was no censure for Gnaeus. He was publicly honoured by Marius and Catulus and awarded Rome’s highest military decoration, the corona graminea. This simple crown of woven grass was reserved for those rare heroes who extricated armies from disaster. Gnaeus’ military talents were inherited by his son. As commander of the government army at Pistoria in 62 BC, Marcus Petreius facilitated the glorious deaths of Gaius Manlius and other old Sullan centurions.

Further Reading

National Museums of Scotland, An Essential Guide to the Declaration of Arbroath

National Records of Scotland, The Declaration of Abroath (text and translation)

A. Keaveney, The Army in the Roman Revolution (London & New York 2007)

Roman Legionary 109-58 BC: The Age of Marius, Sulla and Pompey the Great

This article is a revised version of ‘Before Baculus: Some Sullan Centurions’, Ancient Warfare 14.4 (2021), 40-43