But Two Swords Never

A hoplite armed with a kopis and a xiphos?

According to J.K. Anderson, a hoplite’s offensive weapons consisted of two spears (or spear and javelin), a sword and possibly a dagger, “but two swords never.” Anderson was aware of the depiction of Memnon, a hero of the Trojan War, with two xiphoi (cut-and-thrust swords) on a volute-krater by the Berlin Painter, but concluded that the unusual armament “must be a mistake by the painter; there is no second scabbard” (Anderson 1991, 26 & 37).

Homer does not mention Memnon’s duel with Achilles in the Iliad and only alludes to Memnon in the Odyssey, but other traditions may have noted the hero carried two blades. Swords certainly broke, or were lost in battle, but the practice of carrying a spare was most unusual in the Ancient World. A rare example comes from a fragment of Claudius Quadrigarius’ history, in which it is stated that a Gallic champion was armed with gladios duos (two swords) at the Battle of the Anio in 361 BC.

The Attic pot painters of the late Archaic and Classical eras took great delight in equipping their subjects with the latest military equipment. There was no attempt to depict gods, heroes like Achilles and Memnon, giants or Amazons in archaic arms and armour. They were equipped like contemporary hoplites.

Another master of Attic red-figure, the Triptolemos Painter, took inspiration from the recent Persian Wars. A kylix attributed to the painter shows a hoplite about to bring down his kopis on an unfortunate Persian archer. The kopis (cleaver) was a single edged sword with a curved blade that could hack through armour and sever limbs (Rover 2020). A skull from the Theban mass grave at Chaironeia (338 BC), probably belonging to a member of Sacred Band, was “sliced from temple to temple across the top of the forehead, shearing off the face.” The terrible wound had been inflicted by a Macedonian kopis (Ma 2008, 75-76). Maria Liston describes the blow in graphic detail:

“The blade initially struck the frontal bone, probably near the hairline, at the top right of the forehead. The point of impact is indicated by a small semicircular fracture. The blade continued downward behind the eyes and nose to the top of the mandible, removing the front of the braincase and upper face. The force of the impact created an additional radiating fracture on the right side of the frontal bone, terminating at the coronal suture. This trauma would have been almost instantaneously fatal.” (Liston 2020, 85-87)

The kopis required a wide scabbard to accommodate its distinctive blade, but the Triptolemos Painter has a narrow xiphos-type scabbard hang by the hoplite’s left leg (the upper part is obscured by the hoplite’s shield). Can we assume it was intended to indicate that the triumphant Greek warrior was equipped with a second sword, a slender xiphos?

Archaeological examples of kopides are not uncommon but surviving scabbards and fittings are rare. The ideal scabbard form is illustrated on pots by the Brygos and Kleophrades Painters:

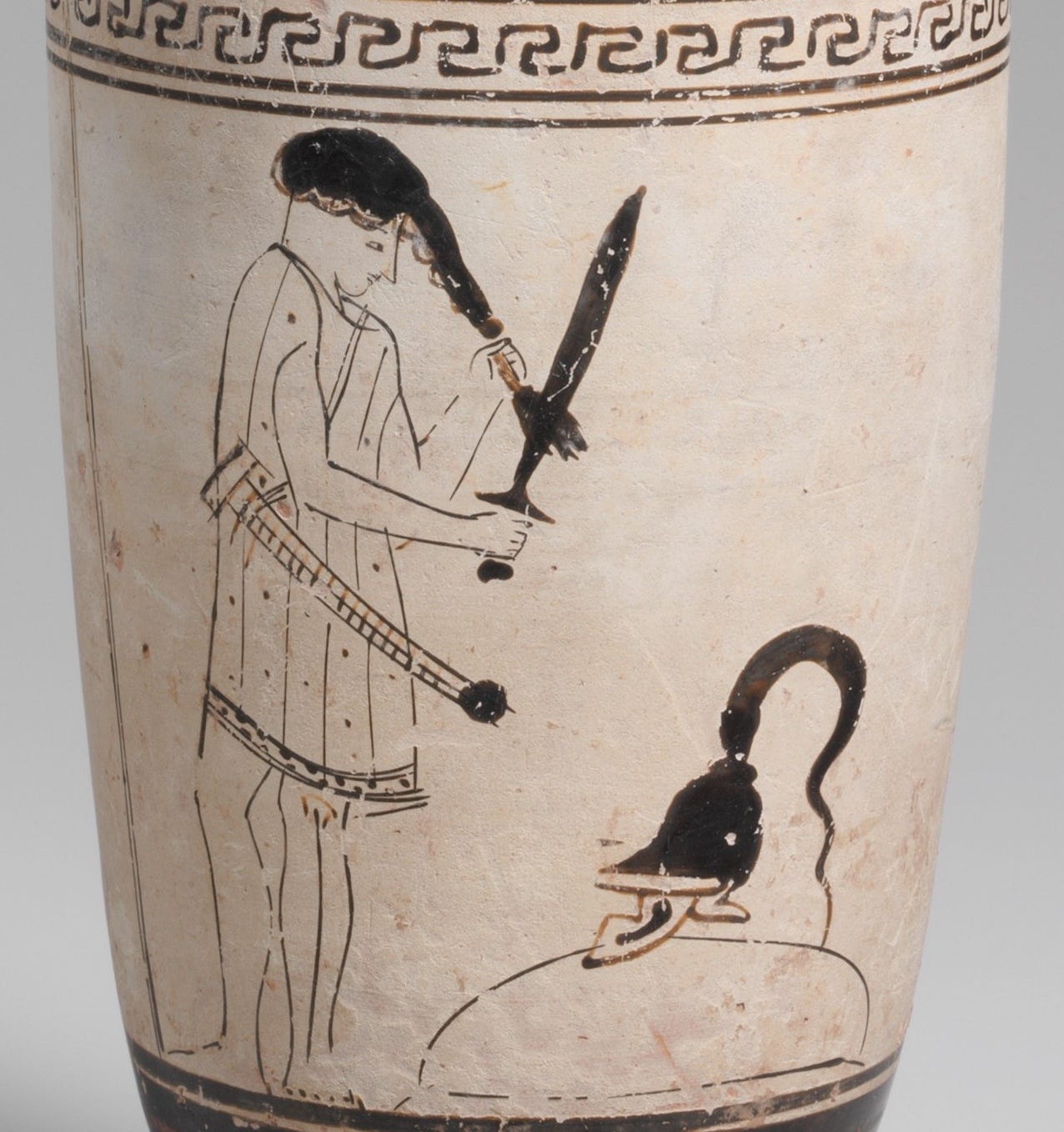

Note, however, that the blade of Neoptolemos’ kopis is actually too big for the scabbard. Undersized scabbards, for xiphoi and kopides, are common on Attic painted pots. For example, on this lekythos a youthful warrior cuts his hair with a xiphos, but the straight-sided scabbard is too narrow for the leaf-bladed sword:

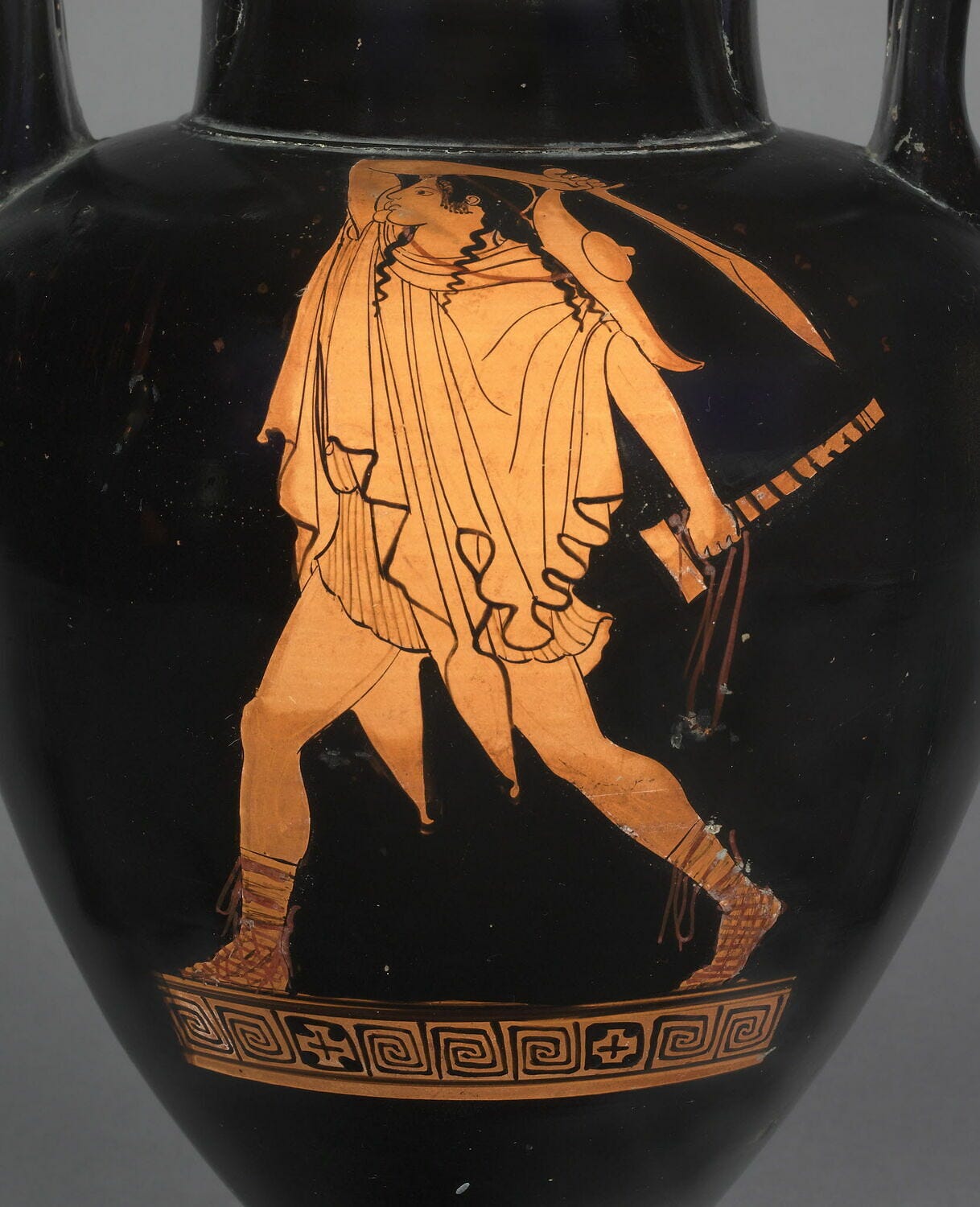

An early red-figure kylix in the British Museum shows Theseus wielding a long kopis (c. 520-510 BC). A straight-sided scabbard is slung from his shoulder. It is broad enough (just!) but too short to hold the complete blade:

On a stamnos by Tyszkiewicz Painter, a hydria by the Leningrad Painter and a lekythos by the Berlin Painter, the scabbards of kopides are of an appropriate length and broad enough at the mouth, but taper towards the chape:

Finally, a neck-amphora by the Providence Painter and shows a kopis in association with a scabbard that is too short and narrow:

Unless such scabbards were split open on one side, which seems unlikely, they could not accommodate kopides.

Returning to the narrow scabbard worn by the kopis-wielding hoplite on the kylix by the Triptolemos Painter, was it intended to suggest the warrior carried a second sword? No. Despite their otherwise accurate depictions of arms and armour, Attic pot painters frequently depicted drawn swords in association with undersized scabbards. The hoplite versus Persian kylix should be considered another example of this artistic convention.

References and Further Reading

J.K. Anderson, ‘Hoplite Weapons and Offensive Arms’ in V.D. Hanson (ed.), Hoplites: The Classical Greek Battle Experience (London 1991), 15-37

J. Ma, ‘Chaironeia 338: Topographies of Commemoration’, Journal of Hellenic Studies 128 (2008), 72-91

C. Parnell, ‘Portrayals and Perceptions: Greek Curved Blades in Black- and Red-Figure Iconography’, Journal of Conflict Studies 8 (2013), 3-21

T.O. Rover, ‘The Combat Archaeology of the Fifth-Century BC Kopis: Hoplite Swordsmanship in the Archaic and Classical Periods’, International Journal of Military History and Historiography 40 (2020), 7-49