Sinful Barbarians and Part-Time Legionaries

The Late Roman Army in Egypt

This article was originally published in Ancient Egypt Magazine in 2006. It’s not one of my favourites, but the subject is interesting and I present it here with some minor changes.

Sometime between AD 425 and 450 Appion, bishop of Syene (mod. Aswan), New Syene and Elephantine, wrote to the emperor Theodosius II to complain that the Roman army was not protecting his churches from the raids of nomads. In the most florid language Appion, optimistically referring to himself as the bishop of the legion of Syene when he was no more than the regimental chaplain, suggested that the emperor transfer command of the legion to him. Thus under his heroic leadership and spiritual guidance ‘the sinful Barbarians, Blemmyes and Nobadae’ would be forcefully persuaded to desist from their ‘stealthy attacks’.

Appion, figuratively prostrating himself before the before the ‘divine and immaculate footsteps’ of the emperor, promised to pray for Theodosius ‘for all time’ if his petition was granted. We do not know if it was. Appion suggests in his petition that the neighbouring bishop of the ‘so-called fortress of Philae’ was about to be granted some form of military authority to enable him to protect his churches, but the mass of papyri relating to the garrison of the First Cataract in the fifth to seventh centuries AD gives no hint that the bishops ever wrested control of army units from the provincial governor, the duke (dux) of the Thebaid.

Appion’s petition seems to add to the impression that the late Roman forces based at the First Cataract were not very good, mere shadows of the glorious legions of the republic and early empire. Indeed, modern scholars have suggested that the legions of Syene and Philae and the regiment of Elephantine (not their original titles but as they are referred to in the fifth-seventh century Elephantine papyri) were little better than part-time policemen, not seriously concerned with soldiering but occupied with making money from civilians and tourists. For example, the predominantly literate soldiers would accept hefty fees to draft and witness official and legal documents for illiterate locals. Some of the soldiers refer to themselves as ‘soldier, by profession a boatman’, suggesting that the latter title was not part of their military duties, i.e. river patrols, but a separate and perhaps primary form of employment. These soldier boatmen may have performed a particular stunt for tourists and travelling officials. It is described by the geographer Strabo who travelled down the Nile in the late first century BC:

A little above Elephantine is the small cataract, on which the boatmen exhibit a kind of spectacle… For the cataract is at the middle of the river, and is a brow of rock, as it were, which is flat on top, so that it receives the river, but ends in a precipice, down which the water crashes; but on either side towards the land there is a stream which generally can be navigated up-stream. Accordingly, the boatmen, having first sailed up here, drift down to the cataract, are thrust along with the boat over the precipice, and escape unharmed, boat and all. (Strabo, Geography 17.1.49)

The Notitia Dignitatum, a late fourth to early fifth century register of all the military commands and administrative offices in the empire, allows us to identify the legion of Syene with the Milites Miliarenses, a legionary unit that probably originated as a 1000-strong detachment from a traditional legion sent to garrison Syene in the late third or early fourth century, but by the time of Appion’s letter was probably only about 400-500 men strong, then average for a unit in the Egyptian army. The regiment of Elephantine was probably the direct descendent of the First Fortunate and Theodosian Cohort formed by Theodosius I (AD 379-395) to garrison Elephantine. The identity of the legion of Philae is discussed below.

Despite doubts as to the military capability of these units, they do have two particular claims to fame. On the various documents drafted and witnessed by members of the First Cataract garrison, the soldiers signed themselves by name, unit and rank. As noted above, the soldiers regularly referred to their units as legions, despite arithmos (the Greek equivalent of Latin numerus - unit or regiment) being the contemporary term. This awareness of their status as legionaries is notable in an age when the historian Procopius had to explain to his readers what a legion was (Buildings 3.4.16). Many of the military witnesses identify themselves on these documents as centurions or ordinarii - another title for centurion - illustrating that, contrary to popular belief, these officers had not disappeared from the late Roman army. This essential officer class, relied upon by Julius Caesar and countless emperors to lead the legions to victory, had been in existence for more than 1000 years!

Other ranks, mostly transliterated from Latin into Greek (or Coptic), are evident on the papyri documents: actuarii (quarter masters); draconarii (standard-bearers); a campidoctor (drill instructor); caballarii (troopers); and a tympanarius (drummer ). [Whatever he did. The early imperial legions relied on trumpeters to sound signals, as did the Roman army of the late sixth century AD, as is made clear by the Strategikon, the tactical manual written by the emperor Maurice. RC 2004]. These ranks suggest that the units were not entirely useless as military organisations but were divided into centuries which were kept supplied and drilled, that the soldiers followed the dragon standards on the march or into action, and had a cavalry element to support them. The caballarii probably escorted the camel caravans that followed the land route from Philae to Syene. This route was also guarded by a continuous wall, some 4-6 metres tall, running from Shellal to Syene; other soldiers must have kept watch from its rampart and watch towers. There is further evidence that the soldiers of the First Cataract garrison were not strangers to military action.

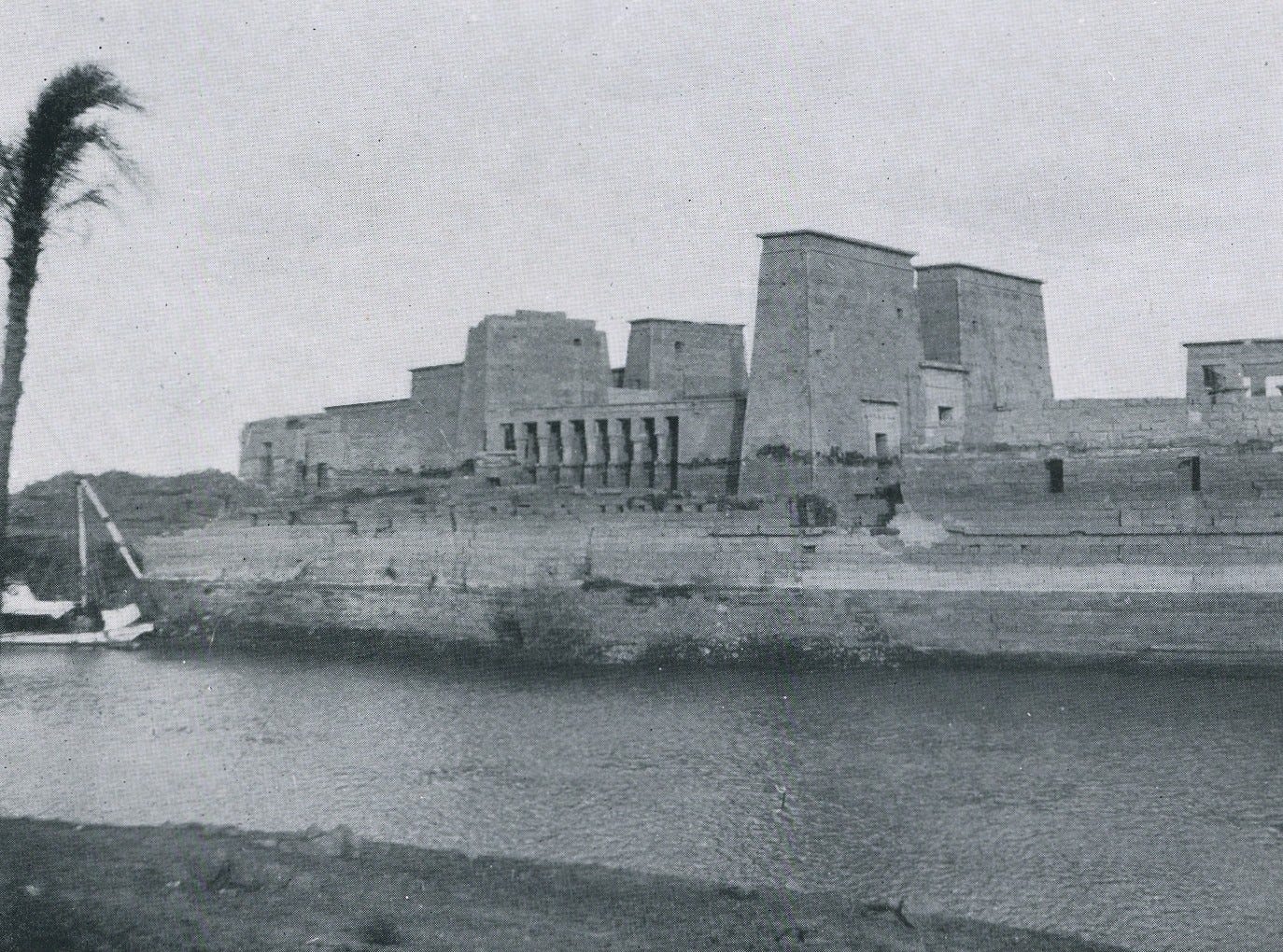

In 1907 British archaeologists were excavating the late Roman fort at Shellal in Egypt, located on the east bank of the Nile opposite the famous temple complex on the island of Philae. The First Cataract of the Nile marked the frontier of late Roman (Byzantine) Egypt and, from the end of the third century AD, Shellal, on the east bank of the Nile opposite Philae, was garrisoned by a specially raised legion, First Maximiana, to guard this strategic point. The legion is later recorded on papyri as the legion of Philae. Hence bishop Appion referred in his petition to the ‘so-called fortress of Philae’ because the fortress and its legion were not actually located on the small island.

The archaeologists uncovered two trenches filled with bodies in the shadow of the tower in the north-east corner of the fort. One trench contained 62 skeletons laid out in three layers; the other trench contained 40 bodies, dumped with less care, and covered with bricks and stones. The skeletons belonged to adult males; only one was aged less than 20 years. A number of the skeletons actually survived with some soft tissue intact and on those skulls which had hair, it was mostly long and wavy. All of the men had suffered extremely violent deaths.

The victims were all bound at the arms and legs with rope. At least one had been decapitated and another partially so, perhaps by an axe but more probably by a sword, and most of the others had been hanged or garroted in such a violent way that the bases of their skulls were fractured. Some bodies still had the nooses around their necks. One man had also been speared from behind with such force that the spear went right through him and emerged at his groin.

All of the bodies showed evidence of severe torture immediately prior to execution: freshly broken bones, sword wounds, and numerous face and head injuries. This kind of treatment was not unusual. While travelling from Rome to Constantinople, the emperor Theodosius I (AD 379-395) is recorded to have captured the scout of a barbarian raiding party and oversaw his ‘laceration with swords’ and beheading (Zosimus 4.48).

The Shellal skeletons were identified by the excavators as Nubian or Blemmyne raiders who had threatened the rich temple complex at Philae at some time during the fourth or fifth centuries AD. Philae was unique in the Christianised late Roman empire. In AD 391 the emperor Theodosius I closed all the pagan temples and shrines but the temples to Isis and other deities at Philae were exempted because of their popularity with the dangerous Blemmyes and Nobadae. In AD 453 the emperor Marcian even allowed the Blemmyes and Nobadae to borrow the cult statue of Isis from Philae. The temples were ultimately closed in AD 536 on the order of emperor Justinian and desecrated by the general Narses. The priests were deported to far away Constantinople.

Perhaps the men in the trenches should be identified as the kind of stealthy church raiders of whom Appion complained to Theodosius? The excavators were hesitant to put a more precise date on the trenches despite the presence of a datable coin in the fill of one of the trenches. The coin is a small bronze of Contantius II showing a Roman infantryman spearing a fallen barbarian horsemen; the legend is ‘Return of the good times’! This coin type was issued by Constantius between AD 350 and 355 but was issued in such great quantities that some examples remained in circulation for more than 200 years, so all the Shellal coin can tell us that the men were not executed before AD 350.

Most interestingly, a considerable proportion of the men in the Shellal trenches had suffered various trauma wounds associated with combat long before they were executed. For example, one man had a sword cut to the back of his skull which was completely healed. These men were not strangers to combat.

It was traditional for Roman soldiers guilty of capital crimes, e.g. cowardice or desertion, to be executed within the confines of the military camp. Is it possible that these men were not tribal warriors but deserters or mutineers from the legion of Philae or another Roman unit? Soldiers were not only recruited locally but also came from beyond the frontier, and the long hair sported by the Shellal victims was intermittently fashionable with the military during the late imperial period. The base of the obelisk in the Hippodrome in Constantinople (AD 390) and the famous Ravenna mosaics (AD 546-47) show the emperors Theodosius I and Justinian surrounded by guardsmen with long hair. If the identification of the Shellal victims as soldiers is correct, they were accordingly executed within the camp as a warning to other soldiers. As was the custom in the Roman army, because these men had broken their military oath and thereby betrayed and endangered fellow-soldiers, former comrades would have carried out their torture and execution (cf. Polybius 6.37). [I’m not so sure about this now! RC 2024]

We will probably never know the precise identity or date of the victims in the Shellal graves. Maybe bishop Appion got his wish and the barbarian raiders who so tormented him were smote hip and thigh. Whatever the case, the graves emphasise that the soldiers based opposite Philae were capable of the brutal violence traditionally associated with the Roman legionary.

The legion of Philae, regiment of Elephantine and the legion of Syene are still attested on papyri dating respectively to AD 601, 611 and 613 (perhaps the latest record of a Roman centurion). What happened to the units after this is not known. They presumably operated against the Persian invaders of Egypt in AD 616-619, and the units might have been reformed when the Romans re-occupied Egypt around AD 630. But within a few years the Roman garrison of Egypt was to face the new power of Islam. The Roman soldiers fought hard but lost. Babylon (Cairo) finally fell after a great siege in AD 641 and in September AD 642 Alexandria was evacuated and the last Roman troops sailed from Egypt. All subsequent attempts by the Romans to retake Alexandria failed.

Thanks to Dr Donal Bateson, Dr Kevin Butcher and Prof. James Keenan for their help with this article.

Further Reading

The Elephanite papyri relating to the legions and Syene, Philae and the regiment of Elephantine, as well as Appion’s petition are translated in full in B. Porten et al, The Elephantine Papyri in English (Leiden 1996), 398-402, 438-602

The size and organisation of the First Cataract units is considered by J.G. Keenan, ‘Evidence for the Byzantine Army in the Syene Papyri’, Bulletin of the Society of Papyrologists 27 (1990), 139-150

The Shellal execution trenches are given brief treatment in G.A. Reisner et al, The Archaeological Survey of Nubia. Report for 1907-1908 (Cairo 1910), vol. 1: 72-73; vol. 2: 100-101, 298-299, 334-336.

For the late legions of Egypt as a whole, discussion of other papyri and continuity of centurions, see A. H. M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, 284-602: A Social, Economic and Administrative Survey (Oxford, 1964), chapter 17. See also my articles on legio V Macedonica, The Last Legion and The Longest Lived Legion.

This article was first published in Ancient Egypt Magazine 35 (April/May 2006)