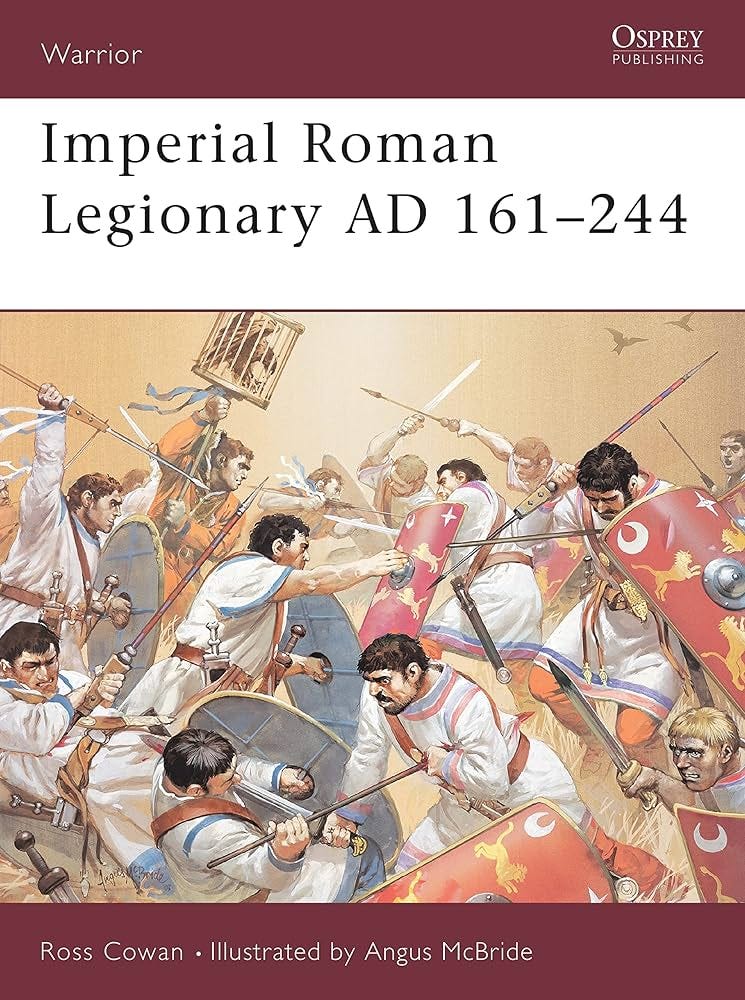

Imperial Roman Legionary AD 161-284 (Osprey 2003) features a dramatic battle scene by the late artist Angus McBride. It depicts a civil war clash of the Praetorian Guard and Second Parthica Legion. Both units were present at the battle between the forces of Macrinus and Elagabalus at Imma on 8 June AD 218. The praetorians fought heroically for Macrinus - until he lost his nerve and fled the field, and Second Parthica sided with Elagabalus, but the positions of units in the opposing lines is not known. It was pure speculation on my part to have the closely-associated regiments collide head-on.

I was not entirely thrilled on learning that Angus McBride was working on the artwork for Roman Legionary 58 BC - AD 69 (Osprey 2003) and Imperial Roman Legionary AD 161-284. If McBride had produced the cover for a heroic fantasy novel by David Gemmell, I probably would have loved it. Imagine mighty Druss, the Captain of the Axe, painted by Angus McBride! But I thought his Conan-esque figures looked ridiculous in historical contexts. My favourite illustrator was, and remains, Peter Connolly, but McBride got the gig and he did a splendid job. (As did Steven Dp Richardson. When photographic permissions could not be secured or licensing fees were prohibitively high, Steven stepped into the breach and quickly prepared sketches of helmets, swords and other relevant artefacts.)

Like all Osprey authors do, I conceived the illustrations and put together design briefs and pictorial reference packages for the artist to work from. The Osprey artist is not required to have any knowledge of the historical period s/he is illustrating. It is not a collaborative process. I had no direct contact with McBride. My editors at Osprey forwarded the design packages to him and I later received A3-sized colour proofs of the artwork from the publisher. Despite my reservations about his style, McBride followed the briefs closely. I was told McBride was an irascible character and would not make changes to his work, but when I asked for minor alterations to a couple of illustrations in Legionary 58 BC - AD 69, he did so quickly and apparently without comment. However, the book went to press with the uncorrected illustrations.

The best illustration in Legionary 58 BC - AD 69 is the last stand of Marcus Caelius and the veterans of the Eighteenth Legion in the Teutoburg Forest (AD 9):

One look at the cenotaph of Caelius tells you everything. The centurion was hard-faced, powerfully built and laden with the most prestigious military decorations for acts of high valour. He was a bellator (warrior). You know that Caelius went down fighting like a true Roman ceturion. McBride captured that defiant warrior spirit perfectly.

McBride was in playful mood when working on the illustrations for Legionary AD 161-284. Dainty birds flit around the feet of Herculean legionaries and a muscle-bound emperor Marcus Aurelius:

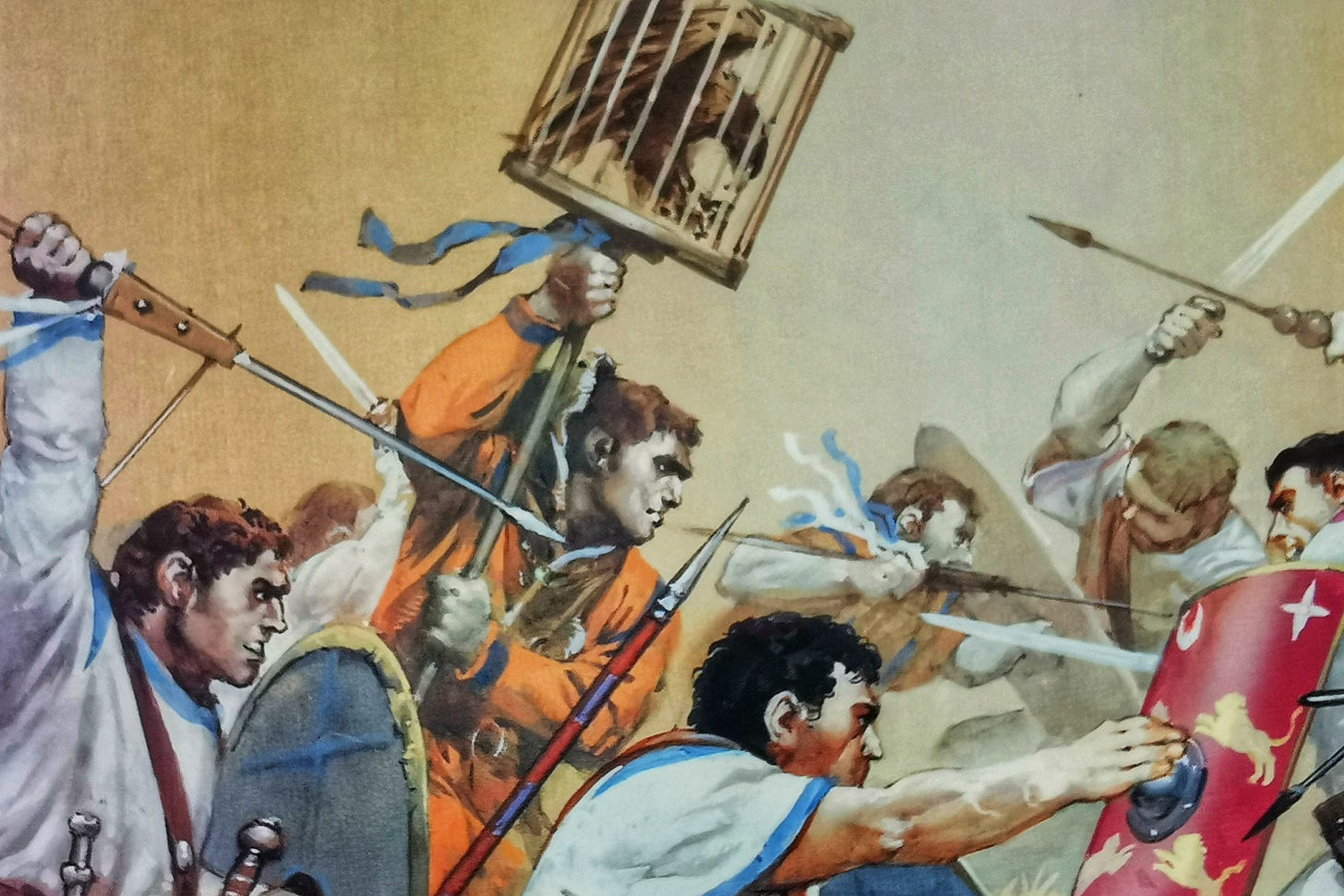

The Battle of Imma illustration was criticised in reviews on Amazon and in discussions on hobbyist forums. That the praetorians and legionaries were presented without armour (suggested by Dio 78.37.4), or even helmets, excited little comment. The problem was the standard carried by the aquilifer of the Second.

Felsonius Verus, a native of Etruria and aquilifer (eagle-bearer) of the Second Parthica Legion, died during the Persian War of Gordian III. He was commerated by his wife, Flavia Magna, at Apamea in Syria (AE 1991, 1572). The fortress of Second Parthica was at Albanum (Albano) near Rome, but Apamea acted as the legion’s base for campaigns against the Parthians in AD 216-218, and the Persians in 231-233 and 242-244 (when Verus died).

Verus’ tombstone was rediscovered by Belgian archaeologists in 1986/87. It depicts the deceased with a most unusual aquila (eagle standard). Instead of the typical shaft topped by a raptor clutching a thunderbolt or a wreath in its talons, Verus’ eagle peeks out of a container with x-shaped bars. The excavators initially considered this “a very strange and aberrant model of an aquila, which deserves more study” but later concluded the eagle was “clearly a live one in a cage” (Balty 1988, 101; Balty & Van Rengen 1993, 12).

I was very taken with Balty and Van Rengen’s interpretation and decided to have Felsonius Verus’ predecessor carry a live eagle mascot into battle in AD 218. Pictures of the Apamea aquila were included in the design package but the artist, perhaps mischievously, or perhaps feeling that an actual bird would not be contained by crossbars, made a notable change. McBride’s bold aquilifer advances determinedly with an eagle hunched in what looks like a modern budgie cage! Cue scowls, and the occasional howl of outrage, from Osprey fans.

The complaints were justified. Felsonius Verus was not in charge of a living eagle. The Roman legions did not have live animal mascots like modern British army regiments. The aquila was the genius (spirit) of the legion, a sacred totem made of silver and plated with gold. What is depicted on Verus’ tombstone is a gilded eagle in a portable aedicula (shrine). The aquila left its aedes (temple) in the fortress only when the complete legion went to war (Dio 40.18.1). The mini-aedicula held by Felsonius Verus acted as a protective case while the legion was on the march but still allowed the sacred statuette to be seen (Stoll 1991).

Other iconography indicates that aedicula-cases were removed and eagles were displayed in their full golden glory in battle. But would Angus McBride’s painting, which also graced the cover of the book, have been so arresting if the aquilifer had carried an aedicula or an uncovered aquila? Probably not.

References

J. Ch. Balty, ‘Apamea in Syria in the Second and Third Centuries AD’, Journal of Roman Studies 78 (1988), 91-104

J. Ch. Balty & W. Van Rengen, Apamea in Syria: The Winter Quarters of Legio II Parthica (Brussels 1993)

O. Stoll, ‘Der Adler im „Käfig“. Zu einer Aquilifer-Grabstele aus Apamea in Syrien’, Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 21 (1991), 535-538. Reprinted with addenda in Römisches Heer und Gesellschaft (Mavors 8) (Stuttgart 2001), 13-46