Warlords and War Bands

Warlords and private armies in Central Italy in the 6th and early 5th centuries BC

What do we know about the war bands, private and gentilicial armies that feature in accounts of warfare in Italy in the sixth and early fifth centuries BC?

An Umbrian Hero

In 1977, Italian archaeologists conducted a rescue excavation in the Italic necropolis of Montericco at Imola. The cemetery was established by the Umbri in the middle of the sixth century BC and was in use for about 150 years. The 77 tombs were organised into rough circles, an arrangement that distinguished the burial places of individual families or gentes (clans). The most important grave in this northern Umbrian outpost belonged to a warrior (von Eles, 1981 127-134).

He was buried in a wooden coffin. Valuable grave goods were placed around the deceased in the interior of the coffin. Directly above his head were two wine jugs, one Etruscan, the other Greek. The latter was Attic and decorated with a scene of Hercules defeating an Amazon. To the side of his skull was an Attic wine cup painted with scenes of a warrior departing for battle.

Between the wine cup and the wall of the coffin were a spearhead and knife. The spearhead was 19.8 cm long, probably a dual-purpose throwing and thrusting weapon. A second spearhead (22.6 cm), was deposited in a bronze wine mixing basin by the man’s right calf. The basin also contained a swallow-tailed bronze brooch. Another small knife was placed beside the basin.

Four silver brooches extended from his neck to his right hand. They presumably once secured garments appropriate to his rank. Other jewellery included two small silver pendants, one on either side of his head. Were they part of a head-dress, or perhaps a necklace that slipped over his face? A small silver ring (1.3 cm in diameter) was placed by his upper left arm, while a somewhat larger bronze ring (1.8 cm) probably graced a finger on his left hand.

Finally, a banqueting set was placed by his feet: a bronze pitcher, various ceramic bowls and dishes, and the remnants of a bronze cheese grater.

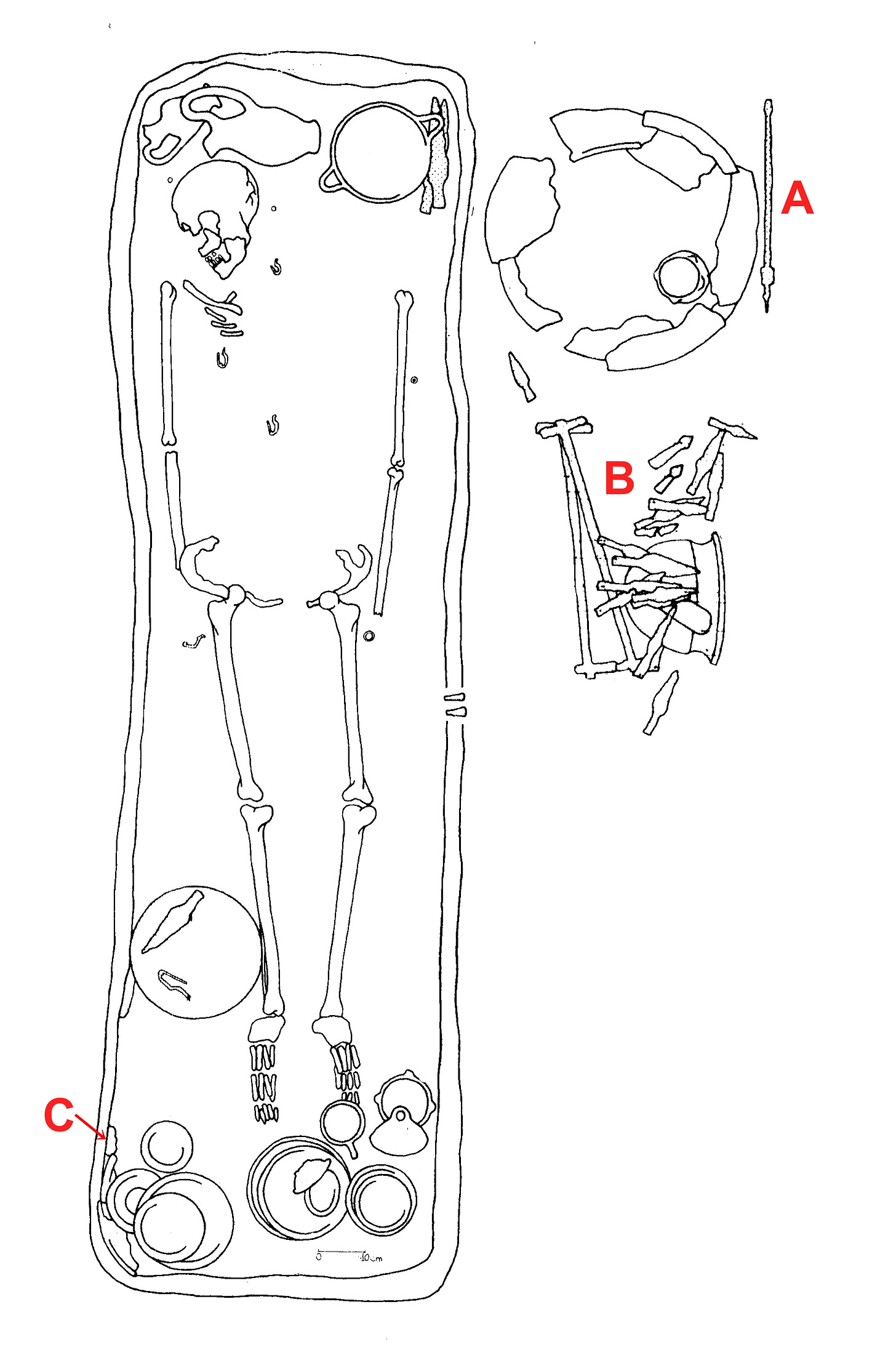

Above: Tomb 72 at Montericco (Imola), c. 480-470 BC. A: Pilum shank (44.5 cm). B: Various spear and javelin heads, Nagau helmet (Belmonte variant), bronze belt fragments and andirons. C: Fragment of cheese grater. Adapted from von Eles 1981, fig. 117)

The contents of the coffin were highly symbolic. The spearheads emphasised the status of the deceased as a warrior. The knives indicated his role as a priest, conducting sacrifices and distributing meat. The brooches and jewellery demonstrated his wealth. So too did the banqueting set, which also served to recall his bountiful largesse and, most importantly, his heroic ideals.

The heroic and military scenes on the Attic wine jug and cup were not coincidental. The spearhead in the wine basin was emblematic the intimate connection between warrior status and the consumption of wine. Like the heroes of the Trojan War, he drank, and distributed, wine with cheese grated into it. This restorative concoction, which also included barley, was known as kykeon and believed to ease the pain of wounds. Just as the ‘princely’ warriors of neighbouring Picenum modelled themselves after the heroic examples of Hercules and the Dioscuri (see Weidig 2021), the occupant of tomb 72 went to the grave with items symbolic of his aspirations, beliefs and conduct during life.

The imported Attic pottery allows us to date the Umbrian warrior’s burial to 480-470 BC, that is during the era of the famous last stand of the Spartans at Thermopylae and the destruction of the Fabii at the Cremera. The Warrior of Montericco lived and died during a heroic age.

A Symbolic Tangle

Intriguingly, two teeth from a pig were placed on the edge of the Warrior of Montericco’s coffin. Heroic and militaristic symbolism can be postulated: that the Umbrian hunted feral pigs or wild boar in imitation of the heroic episode of Meleager and the Calydonian Boar; that the teeth symbolised to the prowess and ferocity the Umbrian had displayed in life; or the boar was his personal emblem.1 The boar was utilised as a standard by Gallic warriors and the pre-Marian Roman legions. It was used as a shield device by the Etruscans of Tarquinii and was frequently incised onto the Italo-Corinthian helmets favoured by warriors in Southern Italy.

Alternatively, the teeth may have come from a sacrifice and feast at the Warrior’s funeral. A dolium, a large earthenware storage vessel, was placed beside the coffin. It contained a cup and was perhaps used a basin for the mixing of kykeon. Beside the dolium was a pilum, perhaps originally with its wooden shaft. This javelin was rather more sophisticated than the usual socketed pila of the period; the long iron shank (44.5 cm) was secured to the shaft by a spike tang and a collet.

Below the dolium was a jumble of spear- and javelin heads (18 in total), two andirons for the roasting of meat, the fragments of bronze military belt and a Negau helmet. What are we to make of this? If the spears and javelins belonged to the Warrior, why were they not placed inside the coffin? Why was he not wearing the military belt? Why was the helmet not inside, or placed on top of, the coffin (cf. Montericco tomb 9)?

Claudio Negrini has suggested that the tangle was symbolic of a warlord and a 17-strong war band: the deceased as “head of the group” represented by the status symbols of belt and helmet, and the war band represented by the spear and javelin heads. It is unclear why Negrini settles on 17 rather than 18 followers. The andirons, indicating feasting and communal consumption, reinforce the image of the band’s comradely cohesion (Negrini 2021, 41-43).

Negrini leaves out the pilum. As a sophisticated example of the weapon and, unlike the other missiles in the tomb, apparently deposited complete with its shaft, it might be associated with the Warrior. It could be considered a particularly heroic weapon. As a heavy javelin designed to punch through shield and armour, he would have had to advance very close to the enemy to use it effectively (see AW XII-6).

Sodales

If Negrini’s interpretation is correct, what was the status of the members of this war band? Naturally, they would be free men of high status like the Warrior himself, but were they members of his immediate family and his wider clan, or were they drawn from elsewhere?

Leaving aside the problematical Haspna of Vetulonia,2 the obvious example of the gentilicial war band is the Fabii who met with disaster at the Cremera River in 477 BC. The 306 Roman aristocrats were drawn from an uncertain number of familiae (families) belonging to the same gens (Fabia). The size of the clan (doubted by some scholars) and the cooperation of its components was exceptional. Compare the war band of another Roman aristocrat. When Maricus Coriolanus went to war in 493 BC, it was not with members of a militarised and unified gens Marcia, but with his personal retinue of close companions, clients and volunteers.

The 306 Fabii were accompanied by their sodales (see below) and clientes, bringing the strength of this private army to 4,000 men - essentially a legion. The clientes (clients, dependents) must have outnumbered the sodales. The clientes were certainly free men and likely had sufficient pedigree and social status to allow them to fight. To use modern terminology, warfare was a middle and upper class affair. Consider how Coriolanus held the plebs of Rome in contempt, and how the poorest citizens were barred from service in the legions.

Coriolanus’ followers were attracted by his charisma, courage and the promise of booty in the form of slaves, cattle and grain. Other raiders sought women or wealthy captives to be held for ransom. Prior to their catastrophic defeat, the followers of the Fabii conducted profitable raids into the territory of Veii. Land was another attraction. The 5,000 armed clients of Attus Clausus, a Sabine warlord, were rewarded with land when they migrated with him to Rome (504 BC). Attus was admitted into the Roman aristocracy, his name Latinised as Appius Claudius. His followers were granted citizenship and settled in a new Claudian district north of the city, where they acted as a buffer against Sabine raids. The followers of the Vibennae and Mastarna gained plots of land in Rome following successful assaults on the city in the mid-sixth century BC.

The Vibenna brothers were Etruscan aristocrats from Vulci but Mastarna may have been a Latin, even a Roman. The nickname Macstrna/Mastarna combines the Etruscanised version of the Latin military title magister (i.e. magister populi, master of the army) with the suffix -na, ‘of’, strongly suggesting that this man was principal lieutenant of the magister or magistri (Maras 2020, 35). Another follower, named Marcus Camitilius (or Camillus), is suspected of being a Latin from Tibur.

The Vibennae were involved in a bloody feud with Gnaeus Tarquinius ‘Rhumach’ - the Roman - who was slain by Marcus Camitilius. Gnaeus was presumably a member of the Tarquin dynasty of Rome, and his band of youthful warriors hailed from from Etrurua (Volsinii and Sovana) and the Faliscan country.

It would not be surprising if the followers of the Vibennae included Faliscans, Sabines and other Central Italian peoples. These peoples spoke distinct languages but proficiency, indeed fluency, in more than one language was not uncommon in polyglot Italy. The Fabii were educated in Caere and thus spoke Etruscan as well as Latin. In a later period, the Messapian soldier and poet Ennius (c. 239-169 BC) was fluent in Oscan, Greek and Latin. For the warlords of the sixth and fifth centuries, the ability to communicate in Etruscan, Latin, Sabine, Faliscan, Greek, and various Sabellic/Oscan languages, whether personally or via interpreters, was essential. (On interpreters, see here.)

The emperor Claudius was a scion of the gens established by Attus Clausus. He was also a keen Etruscologist, and described Mastarna as sodalis fidelissimus, the most faithful companion of Caelius Vibenna. Sodalis means companion or comrade but it also has religious connotations, and it seems likely that sodales swore to follow their leader to the death. The clients and volunteers ranking below the sodales appear bound by oaths of fidelity. According to Claudius, when Caelius Vibenna died, his exercitus (army) remained loyal to Mastarna and followed him to Rome. Yes, army rather than band. The Vibennae operated at a level far beyond that of cattle rustling and low-level raiding, and it is notable how the allegiance of the army transferred to the new magister. Similarly, when Coriolanus defected from Rome to the Volsci, he did not do so alone. His warriors forgot about their Roman citizenship and loyalty to the state, and followed their charismatic and successful leader into the camp of the enemy where, like the followers of Appius Claudius in Rome, one assumes they anticipated being rewarded with land and status.

Claudius tells us that Mastarna marched on Rome and named the Caelian Hill in honour of his friend and former commander. Claudius also believed that Mastarna was identical with Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome. This raises the intriguing possibility that the Servian reforms of the army of Regal Rome were influenced by the organisation of the private army of the Vibennae.

Sodales worshipped appropriately warlike deities. In c. 500 BC, a certain Poplios Valesios and his sodales made a dedication to Mamers (Mars) at Satricum, a town in Latium. Valesios, the archaic Latin form of Valerius, is suspected of being identical with Publius Valerius Publicola, who was consul (chief magistrate) of the newly established Roman Republic in 509-507 and 504 BC. It was he who persuaded Attus Clausus to migrate and thus gained Rome a massive boost in manpower.

Publicola died in 503 BC, but the Satricum dedication suggests that at some point at the close of the sixth century BC he, or a similarly named member of his clan, was operating independently of the Roman state with a private war band. The expedition of the Fabii into the territory of Veii was a private enterprise but had state approval - not that the Roman Senate could have done much to stop it. However, the private army would soon disappear. The activities of Coriolanus and the Fabii represent the last gasps of the phenomenon. Appius Herdonius, another Sabine adventurer, seized the Capitol in Rome in 460 BC, but Coriolanus would have sneered in contempt at Herdonius’ private army: it relied on the manpower of slaves.

Returning to the Warrior of Montericco, we might suppose that the weapons beside the coffin represented 18 sodales, or 19, if the distinctive pilum belonged to a comrade. Just as Mastarna had acted as the lieutenant of Caelius Vibenna, we might assume that the sodales functioned as officers to the rank and file of a potentially much larger war band of clientes. This force presumably had a familial or clan component, but the presence of outsiders, such as other Umbri, Etruscans from nearby Felsina and wandering warriors from further afield, is most likely.3

References and Further Reading

G. Bardelli & R. Graells i Fabregat (eds), Ancient Weapons: New Research on Weapons and Warfare (Mainz 2021)

T. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome : Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (London 1995)

M. Egg, ‘War and Weaponry’ in A. Naso (ed.), Etruscology (Berlin 2017), 165-177

P. von Eles Masi (ed), La Romagna tra VI e IV secolo a.C. (Bologna 1981)

D.F. Maras, ‘Kings and Tablemates. The Political Role of Comrade Associations in Archaic Rome and Etruria’ in L. Aigner-Foresti, P. Amann (eds), Beiträge zur Sozialgeschichte der Etrusker. Akten der internationalen Tagung, Wien, 8.–10.6.2016 (Wien 2018), 91-108

D.F. Maras, ‘Interethnic Mobility and Integration in Pre-Roman Etruria: The Contribution of Onomastics’ in J. Clackson et al. (eds), Migration, Mobility and Language Contact in and Around the Ancient Mediterannean (Cambridge 2020), 23-54

L. Rawlings, ‘Condottieri and Clansmen: Early Italian Raiding, Warfare and the State’ in K. Hopwood (ed.), Organised Crime in Antiquity (Swansea 1999), 97-127

M. Torelli, ‘Bellum in privatam curam (Liv. II, 49,1). Eserciti gentilizi, sodalitates e isonomia aristocratica in Etruria e Lazio arcaici’ in C. Masseria & Donato Loscalzo (eds), Miti di guerra, riti di pace. La guerra e la pace: un confronto interdisciplinare (Bari 2022), 225-234

J. Weidig, ‘The Heroic Virtue of the Warrior’ in Bardelli & Graells i Fabregat (2021), 71-90

This is an extended version of an article originally published in Ancient Warfare 15.5 (2022), 8-11

Cf. the boar scratched beside the name of Aviza Paianiies in the Tomba della Montagnola at Quinto Fiorentino - his personal emblem? See also Maras 2018, 94 & fig. 1.

The c. 150 Negau-type helmets, 55-60 of which were inscribed HASPNAS (‘of/belonging to Haspna’), ritually destroyed and depoisted in a pit on the arx of Vetulonia, are almost certainly spoils taken from a defeated force. Haspna is a gentilicium (clan/family name), and it has been assumed that the inscriptions indicate ownership of equipment supplied to the dependents of the clan. However, it may be that (the) Haspna - as a clan, or perhaps just an individual commander of that name, triumphant in battle, celebrated the glory of the gens by having the gentilcium inscribed on the spoils prior to dedication. The helmets may indicate internecine strife in Vetulonia or conflict with a local foe; the ritual destruction of the helmets - smashed with axes and then crushed - does not necessarily support the internecine proposal. Interestingly, the helmets were depoited in c. 475-450 BC, i.e. around the time of the private military operations of the Fabii in the territory of Veii, and the failed attempt of the Sabine Appius Claudius to seize control of Rome.

A more precise hierarchy for war bands and private armies may be: leader (magister, dux); general staff (sodales fidelissimi, most faithful comrades, headed by the mastarna and rasce); officers (sodales - some perhaps related to the leader, providing a gentilicial element, and other companions, exploiting the aristocratic horizontal mobility, were not necessarily from the same state or ethnic group); warriors (clientes, dependents, mean of limited means but with sufficient social class/heritage to allow them to bear arms; the followers of the Fabii, and of Attus Clausus, were drawn from the same state/ethnicity but in other war bands/private armies, the origins of the rank-and-file may well have been varied). The various elements would in effect be a sodalitas (association of comrades) bound by a political-religious bond of fides. Cf. Torelli 2011, Maras 2018.