An edited version of this article was published in Ancient Warfare 14.1 (2020)

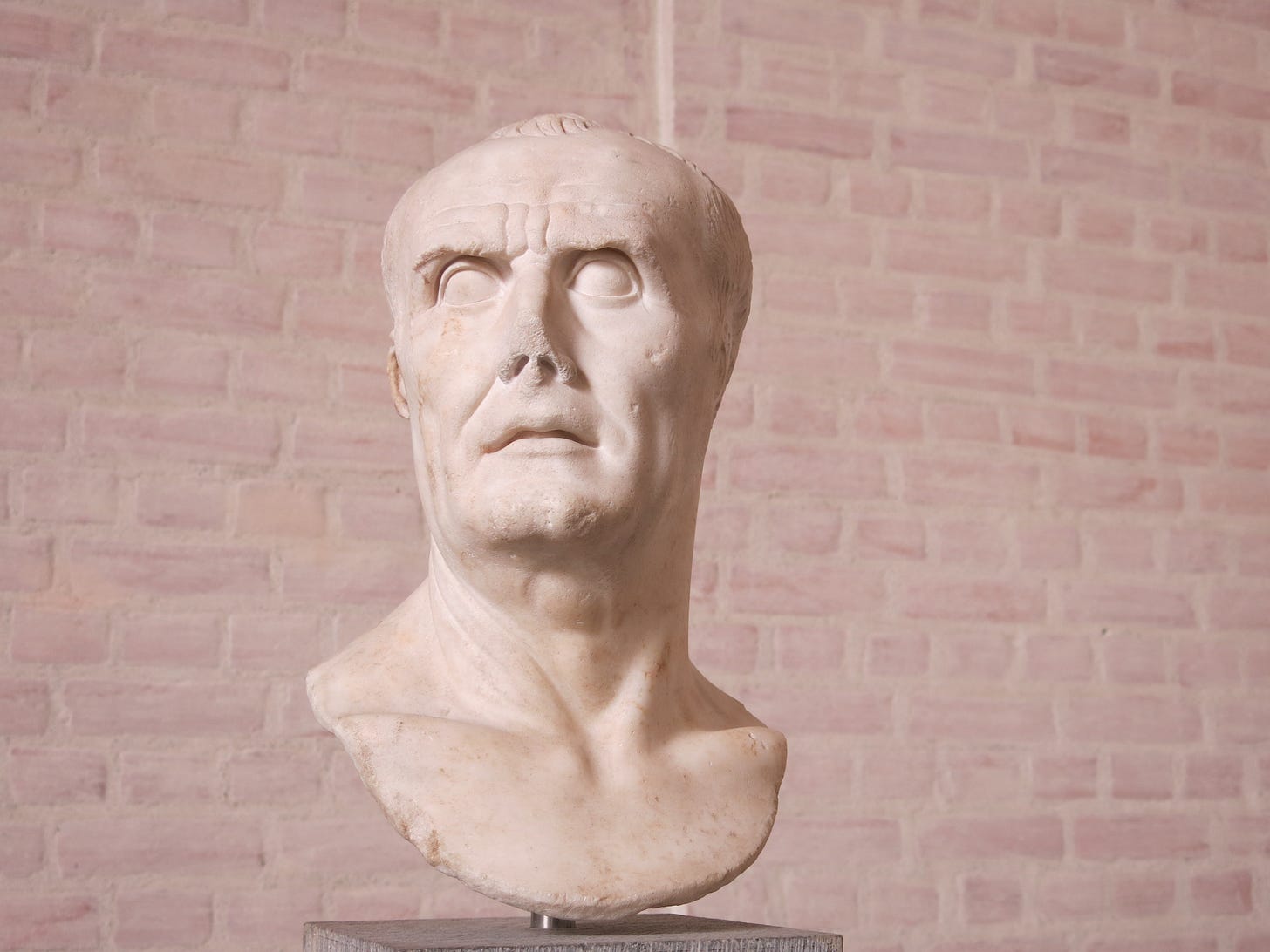

Lucius Sergius Catilina died in the manner of a true Roman hero, hurling himself into the ranks of the enemy. A patrician sprung from the ancient Trojan line of Sergestus, Catiline - as he is better known - was the great-grandson of Marcus Sergius Silus, the warrior who exemplified Roman tenacity in the dark days of the Hannibalic War. Silus famously lost his right hand in battle but returned to the fray equipped with a prosthetic iron fist.

Martial Qualities

The cognomen (nickname) Silus (‘pug-nosed’) was proudly borne by Marcus’ descendants, but the young Lucius broke with tradition and chose a new name. The suggestion that Catiline is derived from catulinus, and indicated an eater of puppy flesh, is absurd. Lucius chose a cognomen that reflected his sharp and shrewd (catus) mind.

Despite being his great political opponent and the architect of his downfall, Marcus Tullius Cicero readily acknowledged Catiline’s brilliance and allure. As young contubernales (tent-mates) in the retinue of the general Pompeius Strabo, they served together in Etruria and Picenum (89 BC). Catiline was probably two years older than Cicero (b. 106 BC) and may have started his military apprenticeship at the very outbreak of the Social War in 91 BC, though not necessarily on the staff of Strabo. Cicero, for example, served first with Strabo and then transferred to the army of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the future dictator, in Campania.

Cicero was impressed by the martial qualities of his contubernalis. He observed Catiline’s energy, endurance, his ability to inspire, and his unusual fencing technique. Instead of striking the usual targets on the torso, Catiline would thrust his blade at face and throat.

Catiline was a Roman blue blood and a conservative. The aspirations of ‘new men’, like the non-noble Cicero, to achieve the consulate – Rome’s supreme annual magistracy – offended him, and his speech exhibited archaic forms. Yet he was not an aloof aristocrat. His charisma and good humour appealed to all classes. He was renowned for loyalty and generosity to his friends and concern for his clients. Catiline was prosecuted for opportune murders carried out under the cover of the Sullan proscriptions, the sacrilegious seduction of a Vestal Virgin (73 BC), and his extreme corruption as governor of Africa. Influential connections, bribery and his ability to deploy charm and win over juries assured acquittal, but Catiline’s ruthless reputation did hamper his political career.

Sulla’s Henchman

On 17 November 89 BC, Pompeius Strabo awarded Roman citizenship, military decorations and double rations to a valiant squadron of Spanish cavalrymen. The witnesses to this ceremony at Ausculum included the contubernales Catiline, Gnaeus Pompeius (i.e. Strabo’s son, Pompey the Great) and Lucius Terentius.

Soon afterwards, on 25 December, Strabo and his army processed through Rome in triumph, displaying their notable captives from Ausculum (including the infant Ventidius Bassus) and spoils. Catiline undoubtedly shared in the glory but did he continue to serve with Strabo in the tumultuous years 88-87 BC? Did he participate in the lynching of Strabo’s distant relative Pompeius Rufus, fight against the Marians at the battle of the Janiculum Hill, and witness (even participate in) Lucius Terentius’ failed plot to assassinate Strabo and Pompey and defect to Cinna?

Despite his reputation as a soldier, little is known about Catiline’s military career between his service with Strabo in Picenum and his last battle in 62 BC. There is no record of Catiline’s involvement in the great military events of 88-82 BC, i.e. the capture of Rome by Sulla and its subsequent fall to Marius and Cinna; Sulla’s campaigns in Greece and Asia against Mithridates of Pontus; Cinna and Carbo’s abortive operation in Liburnia; and Sulla’s return to Italy and victory in the civil war.

Catiline reappears in the aftermath of Sulla’s defeat of the Samnites at the battle of the Colline Gate (1 November 82 BC). Leading a band of head-lopping Gauls, he enthusiastically hunted down and executed Sulla’s proscribed enemies, and enriched himself by seizing their property and possessions. Catiline also settled old scores, carrying out several murders, including that of his sister’s husband, Quintus Caucilius. We might assume that Catiline served under Sulla in the recent civil war and commanded Gallic auxiliaries, but he was probably a Marian.

In 101 BC, Marius, Lutatius Catulus, and Catulus’ legate Sulla, defeated the Cimbri at Vercellae. Catulus had, however, suffered a reverse at the hands of the Cimbri near Tridentum (102 BC), and public opinion held that the hugely popular Marius was solely responsible for the destruction of the barbarian invaders at Vercellae. Catulus grew to hate Marius and opposed him in the civil conflicts of 88-87 BC. When Marius and Cinna triumphed in 87 BC, Catulus was prosecuted by a tribune of the plebs and driven to suicide. That tribune happened to be Marius Gratidianus, the nephew of Marius and the brother of Catiline’s wife.

The younger Catulus naturally sided with Sulla in the civil war of 83-82 BC and demanded retribution. The aged Marius died of natural causes in 86 BC and Cinna was killed by mutinous legionaries in 84 BC, but Gratidianus was very much alive. As a probable recent defector to Sulla, Catiline’s loyalty was tested when he was assigned the task of execution. And no ordinary execution; Catulus wanted a gruesome sacrifice at his father’s tomb. Having already murdered one brother-in-law, Catiline was unfazed by the order to ritually kill another. Cicero noted that Catiline could adapt immediately to any circumstance, and he seized the opportunity to extract a concession from Sulla: the name of Quintus Caucilius was added retrospectively to the proscription list.

Catiline oversaw Gratidianus’ scourging as he was driven through the streets of Rome towards the elder Catulus’ tomb. In an account possibly written by Cicero’s younger brother Quintus, Gratidianus was beaten not with the elm or birch rods used by lictors, but with vine sticks, which indicates the involvement of centurions. When the half-dead Gratidianus arrived at the tomb, Catiline personally took over the torture, breaking his victim’s limbs and gouging out his eyes. The pathetic Gratidianus’ misery finally ended when Catiline hacked off his head with a gladius.

Catiline carried the head, dripping blood, to the Forum and presented it to Sulla. He then washed his hands in a fountain sacred to Apollo. This impious gesture probably outraged Sulla, but Catiline had proved himself a brutally efficient asset and the warlord still had uses for him. In 80 BC, Sulla was busy with the reduction of Italian strongholds. Nola and Aesernia had been in rebel hands since the Social War broke out in 91 BC. Nola fell to Sulla, while Aesernia surrendered to his legate, the ruthless Catiline.

Consul

Sergius Silus was reckoned the best of men. He could not, however, progress his political career beyond the praetorship (197 BC). The Romans revered men of courage, especially those, like Marius, with all their scars to the fronts of their bodies; only cowards who fled from he enemy had scars on their backs. Silus’ missing hand and 22 other wounds sustained in combat were the insignia of glory, but they were extensive and debilitating and therefore aroused distaste. His political opponents implied that such a mutilated man was in fact polluted and unfit to conduct the important religious rites associated with senior magistracies.

Catiline was praetor in 68 BC and governed Africa in 67-66 BC. As was the usual practice, he sought to recoup the huge expenses (largesse and bribes) of his campaign, and to build a fighting fund for his run for consul, by exactions in the province. Catiline went too far and was prosecuted on his return to Rome. He was acquitted, but the prosecution prevented Caroline standing for the consulships of 65 and 64 BC. He then campaigned jointly with Antonius Hybrida for the consulships of 63 BC. The dissolute uncle of Marc Antony served under Sulla in Greece as a cavalry commander, but spent more time plundering than fighting. He was temporarily expelled from the Senate in 70 BC. Quintus Cicero opined that the pair were well matched, except that Hybrida was essentially a coward, whereas Catiline was a man of such extreme virtus (manliness and valour) that he feared nothing, not even the law.

Marcus Cicero, the ‘new man’ from Arpinum (also the birthplace of Marius) and Rome’s foremost lawyer, stood for election. Cicero had considered defending his old contubernalis in 65 BC, but now his own ambition surged and he played dirty: he accused Catiline of plotting to murder senators. True or not, Catiline’s murderous reputation ensured that the accusations stuck. Much to Catiline’s disgust, Cicero and Hybrida were elected, while he was relegated to third place. In June 63 BC, Catiline stood for the consulships of the following year. He attracted support by promising the cancellation of debts, but Cicero again scuppered his chances. The consul appeared at the election with a bodyguard and wearing a cuirass and let it be known that he feared Catiline planned to assassinate him.

The noble Sergii had not produced a consul for centuries. But Catiline had a contingency: the man who feared nothing decided on revolution. The details of the Catilinarian conspiracy of 63 BC need not detain us. The planned coup to kill the consuls and seize Rome was foiled by Cicero. However, using the slogan of debt relief, Catiline’s agents in Etruria had raised two full legions from impoverished Sullan veterans and those left disposed by the Social and civil wars. Catiline was foiled but not yet defeated.

Last Stand

In November 63 BC, Catiline had two full legions (c. 10,000 men) at Faesulae, but only a quarter of the men were fully armed. A small senatorial army under Marcius Rex was already in the vicinity of Faesulae, but posed no real threat. When Hybrida’s consular army arrived in late November. Catiline broke camp and marched through the wintry hills north of Faesulae, denying Hybrida any opportunity for battle, but supplies and morale ran low. In mid-December came the news that Cicero had successfully exposed the plot to seize Rome and executed Catiline’s co-conspirators. Yet another army, consisting of three legions under Metellus Celer, was positioned to intercept the rebels if they crossed the Apennines. The position looked hopeless and some 7,000 rebels abandoned Catiline. However, the remaining 3,000 were his choicest troops: Sullan centurions, evocati (veterans invited to resume service under their old commander) and lecti (chosen men). Catiline’s liberti (freedmen) and the coloni (tenants) from his estates in Etruria did not desert him. He honoured them in turn by organising them as a bodyguard - essentially his praetorian cohort.

Unable to cross the Apennines (presumably by the Poretta Pass and the valley of the Reno), for the ‘secret routes’ he favoured were revealed to senatorial forces by the deserters, Catiline finally marched into the high country above Pistoria (Montagna Pistoiese) and decided to make a stand. He would either cut his way through Hybrida’s army or die fighting like a hero. By 3 January 62 BC the small army had exhausted its supplies and Catiline assembled the remaining legionaries and exhorted them. Mostly veterans, they were under no illusions about the likely outcome of the battle. They were vastly outnumbered but determined to die well and preserve their pristine reputations for virtus.

Catiline had the trumpeters sound the signals and led the legionaries in battle order to a pre-selected site near Hybrida’s camp. With so few troops, Catiline had to turn the terrain to his advantage. His chosen battlefield was a narrow plain, secured on the left by the mountains and on the right by broken, rocky ground. Campo Tizzoro and nearby Pontepetri are the traditional locations for battle. Eight cohorts filled the plain and formed Catiline’s main battle line. The remaining legionaries were held in reserve beneath their standards, but Catiline withdrew the all the centurions, lecti, evocati and best equipped men and placed them in the front line. He sent away his horse and those of his officers to show that the danger would be the same for all.

Catiline and his bodyguard took up position at the centre of the battle line. He had with him a Marian aquila from the Cimbric War. Gaius Manlius, a former Sullan centurion, commanded the right wing and a ‘man of Faesulae’, probably a Sullan veteran named Publius Furius, commanded the left.

Hybrida did not venture out of his tent. He was apparently suffering an ailment of the feet (perhaps gout), but it may be that he deliberately drank himself insensible. Command was assumed by the legate Marcus Petreius. He was a formidable character with more than 30 years’ military service. It is likely that his father was the hero Gnaeus Petreius. As senior centurion in the army of the elder Catulus, Gnaeus executed a cowardly military tribune, assumed command of a legion and saved it from destruction by the Cimbri.

Petreius was suspicious of Catiline’s move. He sent scouts to reconnoitre but no ambush or ruse was detected. Catiline offered a head-on collision of legions and Petreius accepted, promptly formed his battle lines with re-enlisted veterans at the front. He exhorted them, many he knew by name from previous campaigns, sounded the signal and then led them slowly towards the enemy.

Catiline did the same but when his legionaries came into range, instead of pausing to hurl their pila, they dropped the javelins, drew their swords and charged. Petreius’ veterans were shocked by the rebels’ fury. Catiline’s warriors would not give ground. In a manner reminiscent of King Pyrrhus at Heraclea (280 BC), Catiline both fought and directed the fighting, sending reinforcements to weak spots in the line and ensuring the wounded were carried to the rear. Petreius’ army could make no headway and the legate (still on horseback in order to have a better view of the field) called in his own praetorian cohort of elite legionaries. It collided with the centre of Catiline’s army and pushed it back; the praetorian cohort then split, driving right and left to assault the wings of the rebel army. Manlius and the man from Faesulae died fighting. Their legionaries refused to retreat and were killed where they stood.

The centre of Catiline’s army was indeed forced back but these men, veterans, freedmen and farm tenants, would step back only so far and also died with their wounds to the front. Catiline charged into ranks of the enemy, hacking and stabbing until he fell mortally wounded. He was later found beneath a heap of Petreius’ legionaries. His body was taken to Rome and, for a time, his tomb was a site of veneration.

Of Catiline’s 3,000, not one of the free-born legionaries survived: death before dishonour. Such was the mauling inflicted on Petreius’ army that it was a ‘joyless victory’ for the Roman Republic. Interestingly, some of the freedmen, perhaps those in the ill-equipped second line, did escape the slaughter.

These former slaves took the personal and clan name of their patron. One Lucius Sergius reappeared soon afterwards in Rome as a heavy in the retinue of the radical politician Clodius. The freedman’s cognomen is not known, but he was notorious for having been Catiline’s armiger (armour-bearer) – presumably at the battle near Pistoria. Another ‘Lucius Sergius, freedman of Lucius’, settled at Amiternum in the Sabine country and, most unusually, married a free-born woman. It has been proposed that he was not only a survivor of the battle but supplied eye-witness details to Sallust, a native of Amiternum and the author of The War With Catiline.1

The Eagle

What of the eagle standard, the silver aquila? Sallust tells us only that it was a Marian relic from the Cimbric War. As a symbol of Jupiter and Rome, the eagle lent legitimacy to Catiline. When he denounced Catiline in the Senate, Cicero revealed that Catiline had created a sacrarium (a room for sacred objects) in his house for the eagle and worshipped it. When Catiline departed Rome for Etruria (there was not yet sufficient evidence to detain him), Cicero reported that he sent ahead weapons, fasces (rods and axes, the symbols of magisterial authority), trumpets, military standards and “that silver eagle” to his lieutenant Manlius. Cicero was clearly dismayed that Catiline possessed such a totem.

Where did Catiline acquire the aquila? How long had it been in his possession? Did he inherit through his marriage connection to Marius? Did he plunder it from a temple or a shrine during the civil wars or the Sullan proscriptions? Did he capture it in battle? The legions of the Late Republic were not permanent formations, but so many legions were raised in the 80s BC that, as well as new standards being made, old eagle standards may have been retrieved from shrines. And what happened to it when Catiline was defeated? Marius established the aquila as the standard of the legion in 104 BC. Catiline venerated his silver eagle and his army rallied around it. In the 50s and 40s BC, Julius Caesar’s soldiers were willing to die for the eagles of their legions. The aquila was obviously a sacred and potent object and an important prize in war. It is not certain that Petreius captured Catiline’s eagle. Cicero and Sallust are silent about its fate. Was it whisked away by one of the freedmen who escaped? We will never know.

Further reading

Roman Legionary 109-58 BC: The Age of Marius, Sulla and Pompey the Great