The Lost Legion

In The Fate of the Ninth, Duncan B. Campbell dismantles the myth, essentially created by Theodor Mommsen, that the Ninth Legion was annihilated at some point between AD 108 (when it is last attested at its HQ in York) and 120 (the start of Hadrian’s reign was marked by some upheaval and fighting in Britannia).

Mommsen suggested the legion was destroyed by revolting Brigantes or even – and quite anachronistically – by the Picts and Scots. The great scholar’s influence assured that the theory of the legion’s destruction in northern Britain was accepted as a fact in academia. This spilled over into the public consciousness. In 1954, the publication of Rosemary Sutcliff’s The Eagle of the Ninth cemented the popular perception of the Caledonians being the agents of the legion’s apparent destruction in AD 117 (her preferred date). However, the careers of officers whose service in the legion occurred *after* this apparent calamity demonstrate that the Ninth was alive and well in the AD 120s and beyond.

Aemilius Karus was a tribune in the legion at some point between AD 122 and 127, and Novius Crispinus’ tribunate cannot be dated before AD 128. But the Ninth was clearly no longer based at York, or even resident in Britain. It played no part in the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. By the AD 120s, the legion had relocated to Nijmegen, where its presence is evidenced by tile stamps and other epigraphic material. When exactly it arrived there (perhaps following a sojourn at Carlisle) is a matter of dispute.

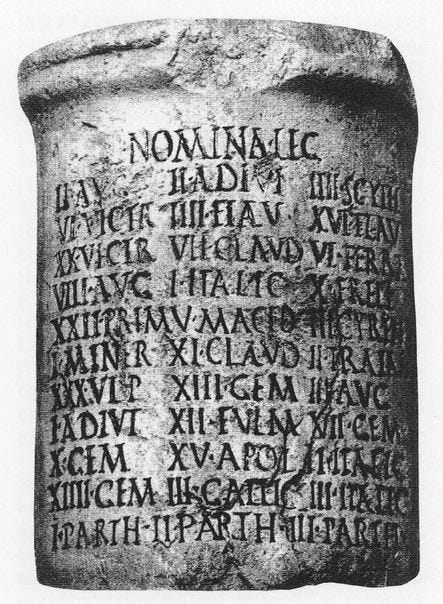

The legion may have been sent east to fight in the Jewish revolt of AD 132-5, and was perhaps reinforced by a draft of marines from the fleet at Misenum. Did the legion meet its fate in this war? No. It was still in existence in AD 140/1 when Numisius Iunior began his tenure as tribune, but the Ninth was not listed on the Nomina Legionum (‘The Names of the Legions’) columns, set up in Rome shortly before AD 165.

With this possible end date in mind, and assuming that the legion remained in the East after its apparent service in the Jewish War, could the famous battle of Elegeia, where the Parthians destroyed an unnamed Roman legion in AD 161, account for the disappearance of the Ninth? Perhaps, but other legions are missing from the Nomina Legionum and Campbell prefers to await the discovery of fresh epigraphic evidence (i.e. epitaphs, career inscriptions, dedications, building inscriptions and tile stamps) that will confirm the movements of the Ninth and provide firm dates for the service of its officers and lower ranks.

Campbell is certain that the Ninth was not disbanded in disgrace, the fate suggested for it by Ian Richmond, the renowned British archaeologist. Richmond believed the legion was cashiered by Hadrian after suffering a disgraceful defeat in what is now south-western Scotland. But compare the treatment of the Third Legion Augusta. Disbanded by Gordian III for its role in the defeat and deaths of Gordian I and II in Africa in AD 238, the Third suffered damnatio memoriae and its numeral and title were erased from all monuments. Such damage is absent from the inscriptions of the Ninth.

Campbell’s elegant book is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of the Roman army, and in how that history is revealed by the careful study of epigraphy and archaeology. It is a necessary academic antidote to Simon Elliott’s Roman Britain’s Missing Legion, the ‘Exit the IXth’ chapter in John H. Reid’s The Eagle and the Bear, and all the others yet to emerge from the shadows of Mommsen and Sutcliff.

Duncan B. Campbell, The Fate of the Ninth: The Curious Case of the Disappearance of One of Rome’s Legions